Banks, Bomb Detectors, and Bullshit: UK-Mexican Relations and the War on Drugs

In 2015, officials, businessmen, and a handful of intellectuals, academics and authors celebrated the Dual Year of the United Kingdom and Mexico. The cultural and gastronomic festivities provided a thin veneer to what was essentially a jamboree devoted to free trade. In a series of public events and private meetings UK and Mexican bureaucrats stressed the need for increased bilateral trade.[1] Perhaps unintentionally, the Mexican president led the way, bringing over a retinue of 200 family members, civil servants, and hangers on, who proceeded to spend vast sums of money in London’s designer shops.[2] But, others soon followed. And in the private sector, the leaders of one of the UK’s lone globally completive industries – the arms trade – used the opportunity to line their pockets. In the same year in which Mexican armed forces were accused of extra-judicial killings in Tlatlaya, Zacatecas, Apatzingan, Tanhuato and Ayotzinapa, London’s Defence & Security Equipment International (DSEi) arms fair welcomed a large delegation of Mexican military personnel; twenty British weapons companies signed new export deals with Mexico; and sales of arms equipment to Mexico rose 6000 per cent from £2.6 million to £157 million.[3]

Such profiteering is nothing new. In fact, the UK has a long history of exploiting both the drug trade and the war on drugs. During the nineteenth century, the UK used opium imports to open up the Chinese markets and fought two wars in order to maintain the trade.[4] And over the past thirty years, the City has been at the centre of laundering money from illegal narcotics.[5] It is clear that both the drug trade and the war on drugs offer enormous financial rewards, not simply for entrepreneurial young Mexicans, keen to leave lives of grinding poverty and limited opportunities, but also for large multinational companies. In this article I look at how three British companies, supported by the British government, sought to profit from drug trafficking and the efforts to stop it. The three stories focus on HSBC, the GT200 bomb detector, and somewhat less obviously, the Hay Literary Festival. In doing so, I hope to demonstrate the manner in which international firms have sought to profit from the drug trade, show how the UK and US governments have supported – or at least refused to prosecute - these efforts, and highlight how cultural perceptions of the drug trade have helped create a two-tier justice system both in Mexico and abroad.

HSBC: The World’s Local Bank

In summer 2012, a US Senate investigation found that the British banking giant, HSBC, had “opened a gateway for terrorists to gain access to US dollars and the US financial system” and repeatedly failed to apply anti-money laundering controls to millions of dollars from drug trafficking organizations. According to the report, it had not only provided space for terrorist-linked business to move their money around, it had laundered at least $881 million from drug traffickers in Mexico and Colombia alone. In an act of supposed strength, the US Department of Justice fined the bank a record $1.92 billion.[6] If the facts of the case are pretty clear, the details are not. And it is in the details, buried within the tortuous and complicated report where we can see not only how HSBC laundered the money, but also how it evaded the regulators for so long.

Money laundering is key to the smooth functioning of the world’s larger drug trafficking operations. In Mexico, organizations like the Gulf Cartel, the Zetas, the Sinaloa Federation, and the Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación need clean money to reinvest in the drug industry (buying warehouses, vehicles, chemicals or weapons), to bribe local government and law enforcement agents, and to buy up legal businesses. When Mexican forces captured Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán (for the third time), the US government released information, which linked the cartel head to 288 businesses in ten countries. They ranged from small-scale local firms, like gas stations, restaurants, pharmacies, real estate companies, and Cuiliacán’s “Race Park” racetrack, through medium sized concerns like the mining speculator Nueva Generación, to complex multinationals including Miami-based financial firms and an Ecuadorian airline.[7] Laundering drug money involves three essential phases. The first is “placing” - that is introducing the illicit funds into the financial system or in layman’s terms opening an account. The second is “layering” or putting these funds through a series of financial transactions to conceal their origins. This can involve wiring the money from account to account, transferring the money into travellers’ cheques, or moving the cash from country to country. The third is “integration” or reintroducing these supposedly legitimate funds into the legal economy through purchasing businesses, real estate, high-end products, or investments.[8] Laundering is a massive multibillion-dollar business, which few social scientists have tried to quantify. But one of the few studies of efforts in Colombia indicates that as much as 97.4 per cent of the sale value of cocaine leaves the country and is washed through international firms and financial organizations.[9]

In Mexico, HSBC was involved in all stages of the money laundering process. At the most basic level, both traffickers and frontmen for trafficking organizations could open accounts in HSBC’s Mexican branches with little or no investigation into where the money originated. The Department of Justice claimed that traffickers had even manufactured specially-shaped containers designed to fit through the bank tellers’ windows. As late as 2008, the bank’s own survey estimated that as many as 75 per cent of high-risk clients still lacked proper investigation. And in 2009 Mexico’s own anti-money laundering regulator ordered the bank to shut 3600 accounts of which 675 were explicitly linked to drug traffickers. Many of these clients gravitated towards HSBC Mexico’s exclusive Cayman Islands accounts. Between 2005 and 2008, the number of accounts increased from 1500 to 60,000 and totalled $2.1 billion. Here, anti-money laundering practices were even more slapdash. As many as 50 per cent of the accounts lacked the basic “visit report” (the cornerstone of finding out where the money comes from) and 15 per cent had no files at all.[10]

Such minimal investigations made for some interesting clients. Many were linked to the Sinaloa Federation.[11] During the early 2000s Sandra Avila Beltran, (aka The Queen of the Pacific), was treasurer of the organization. She employed various ways to wash the cartel’s money including claiming that the cash came from over-the-counter transactions at the local money exchange - the Casa de Cambio Puebla.[12] The front was a big customer of HSBC Mexico, had a dollar account with HSBC US, and had even brokered a loan with the bank. During this period, the bank’s Mexican and US branches repeatedly made excuses for the massive increases in note traffic from Puebla. For example, when intakes increased from $27 million in September 2005 to $76 million in September 2006, bank officials argued that this was due to the high-income levels of returning farm labourers. In fact, even though Mexican authorities moved against the currency exchange in early 2007, HSBC continued operating the accounts until November that year. Between January and October 2007, the company made 170 wire transactions totalling $7.3 million.[13]

Others customers were more autonomous freelancers. In 2007, the Mexican police raided the plush residence of Chinese-Mexican entrepreneur Zhenly Ye Gon where they discovered a cache of firearms, $18 million in Mexican pesos and a staggering $205 million US dollars, apparently the largest cash seizure ever in a drug sting. They accused Ye Ghon of purchasing and importing ephedrine precursor chemicals – vital for the production of methamphetamine – into Mexico between 2005 and 2006. During the investigations, they found that he had used HSBC to deposit and move his money. In fact, as early as 2003 HSBC’s own anti-money laundering specialists had demanded the Mexican branch terminate the relationship. But HSBC Mexico had simply neglected to do so and over the next three years he moved $50 million via the bank.[14]

If HSBC’s Mexican branch provided space to deposit or “place” cash, its links to HSBC’s US branch allowed drug traffickers to “layer” their cash and “integrate” it into legitimate businesses. These links were particularly important after the tightening up of the US’s money-laundering regulations post-9-11. Moving money from HSBC Mexico to HSBC US became one of the easiest ways to move clean cash out of the country and into the global economy. The mechanics of these transfers were threefold. First, traffickers or front men simply entered HSBC Mexico branches, handed over wads of illicit dollars and demanded their equivalent amount in US travellers’ cheques. These cheques, which were processed using HSBC US accounts, could then be exchanged for clean money. During the early 2000s, this was a burgeoning business. In the third quarter of 2004, for example, HSBC Mexico sold $110 million of travellers’ cheques. The amount totalled more than any HSBC branch office, even eclipsing the massive amounts handed out by HSBC Europe’s UK centre. In fact, the sum represented a third of group’s total global travellers cheque business.[15]

Second, traffickers used HSBC Mexico’s links to its US partner to move vast quantities of physical banknotes in armoured cars or planes from Mexico to its northern neighbour. Again, this was big business. In 2007 HSBC US accepted $3 billion in physical notes from its Mexican branches. The following year, it accepted over $4 billion. In fact, in February 2008 the Mexican regulator informed HSBC that it was repatriating more dollars than any bank in Mexico, including its four larger competitors. Many of these repatriations were made by drug trafficking fronts. Between November 2007 and February 2007, HSBC US purchased $196 million from the Sinaloa Cartel-run Casa de Cambio Puebla. Somewhat oddly for a supposed money exchange business, in the same period it sold the company nothing. Despite these discrepancies, HSBC’s Mexican and US divisions did nothing. In fact, between 2006 and 2009 HSBC US actually stopped monitoring HSBC affiliates’ dollars transfers at all. The Senate reported that they could offer no explanation.[16]

Third, HSBC became the conduit for a complex and intensive process of laundering – a long washing machine cycle if you will – called the Black Market Peso Exchange or BMPE. The BMPE not only layers drug cash, it also integrates it into the legitimate financial world. This was employed by Colombian trafficking organizations, particularly the Norte del Valle cartel, because of the strict Colombian regulations governing depositing dollars in local accounts. But, like the Mexican cartels’ strategies, it also involved HSBC Mexico. According to the Department of Justice, the process worked as follows. First the traffickers sold their drugs in the US, smuggled the money into Mexico, and deposited it in HSBC Mexico account. Once the money was “placed” they then sold their dollar profits to brokers for a discounted rate in Colombian pesos. These brokers then took orders from legitimate Colombian businessmen for foreign products. In return, these businessmen paid the brokers in pesos. The brokers then arranged for the foreign goods to be bought with the drug money stored in HSBC Mexico accounts. The goods were then brought back to Colombian and sold by the businessmen. In the end, everyone won. The businessmen obtained dollars at a lower exchange rate than otherwise available, the Colombian cartel leaders received Colombian pesos, and the brokers received fees as middlemen.[17]

The question remains, how did HSBC allow this to happen? Since 2000 both U.S. and Mexican regulators have brought in increasingly stringent controls designed to curb money laundering. Yet, in both countries, HSBC was able to avoid these regulations on a sustained basis. HSBC Mexico, in particular, was rotten since its inception. In 2002 HSBC bought the Mexican Banco Internacional S.A, part of the Grupo Financiero Bital S.A. At the time, Banco Bital had no effective anti money laundering department or procedures. As recently as 1998, Bital had been flagged as one of Mexico’s leading narco banks by a joint DEA and Treasury investigation, codenamed Casablanca. The Federal Reserve charged that Bital, together with Banamex and Banco Santander, had “serious deficiencies in their money laundering programs”. And HSBC knew it. A pre-purchase audit of the bank found that compliance and money laundering functions were “non-existent”. Nearly half of Bital’s offshore Cayman Islands accounts had no client information whatsoever. Despite these revelations, HSBC’s man in Mexico – Alexander “Sandy” Flockhart – pushed through the purchase of the bank. According to a UK Foreign Office employee, who knew Flockhart at the time, the banker refused to do even the most basic checks. “It was the early 2000s, everything was for sale and he didn’t want to miss out”.[18]

Over the next decade, HSBC Mexico grew substantially. Yet, problems with the anti-money laundering program remained. As late as 2008 the new head of HSBC Mexico, Paul Thurston admitted that there was a “lack of compliance culture” at the bank.[19] Branch employees opened accounts without proof of ID and failed to do rudimentary “Know your Customer Checks”. But, such practices also reached further up the bank hierarchy. One HSBC Mexico whistleblower disclosed that between July and December 2004 the bank’s compliance officials had fabricated records of mandatory monthly meetings by the bank’s internal compliance committee and provided false records to the regulator. They were fabricated at the behest of the bank’s money anti-money laundering director, Carlos Rochin. Beyond negligence and overt corruption, HSBC Mexico’s leaders were also extremely slow to close down avenues for potential money laundering, even when they were directly pointed out to the bank by the regulator. After the Casa de Cambio Puebla scandal, the bank took nearly a year to stop the organization processing money through its accounts. And after another money exchange company, the Sigue Corporation, was prosecuted in the US for laundering cash, Thurston decided to keep the account against the advice of HSBC’s own compliance division.[20]

But HSBC’s problems did not end in Mexico. As the Senate report makes clear, by providing access to US dollars and US markets, HSBC U.S. branch was equally complicit. On the most basic level, HSBC US repeatedly gave its Mexican affiliate a low risk rating. As a result, it neglected to implement more stringent checks on dodgy transactions. This took substantial effort. To maintain Mexico as a low risk client, HSBC’s risk analysts were forced to ignore almost every external risk assessment including annual US State Department warnings, a 2005 multiagency Money Laundering Threat Assessment Report, a 2006 Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCen) admonition, the high-profile 2008 Watchovia money laundering case, and a US regulatory cease and desist order. The 2006 FinCen admonition alone should have added ten points to Mexico’s risk rating, automatically placing the affiliate in the high-risk category. But, risk analysts “forget” to add it to the company’s score. HSBC US’s risk analysts not only had to disregard the most basic federal advice, they also had to remain deaf to their own internal reports. In 2009, the head of HSBC Group’s Anti-Money Laundering Compliance division singled out Mexico in an email to the HSBC Group Compliance head, David Bagley. Here, she pointed out that “there [we]re specific risks in relation to pressure from the US with regard to the laundering of the proceeds of drug trafficking through Mexican cas[a]s de cambios.” Nevertheless, a few months later Mexico received another low rating. Bagely subsequently admitted that he could have informed HSBC US about issues with the Mexican affiliate but “we did not think of it”.[21]

HSBC US’s problems with money laundering permeated all levels of the organization. At the top end, anti-money laundering chiefs were either ignorant and incompetent or relatively efficient and, as a result, ignored. The turnover of roles was unsurprisingly high. Between 2007 and 2012, the company had four compliance heads and five anti-money laundering directors. The Federal Reserve concluded that at least one, Lesley Midzain “did not possess the technical knowledge or industry experience to continue as the … AML [Anti-money laundering] officer”. The US regulator concurred. But in 2007, the bank gave her a new dual role as both compliance and anti-money laundering head. When the former US Treasury official, Wyndham Clark, took over the role in late 2009, he discovered that the bank had an “extremely high risk business model from a AML perspective”. His concerns, complaints, and requests for more staff were repeatedly ignored. And after less than a year, he resigned. In his letter to Compliance head, Bagley, he directly blamed HSBC’s chiefs for the poor efforts of his division. “Most of the critical decisions in Compliance and AML are being made by senior management who have minimal experience in compliance, AML, or our regulatory environment”.[22]

What the Senate report rather euphemistically terms “leadership problems” translated into an almost comically incompetent anti-money laundering department. On the one hand, the department was chronically understaffed. From 2006 to 2009 HSBC US’s entire compliance department comprised 200 out of a total of 16,000 employees. The US regulator repeatedly complained about this, but was ignored. And when the HSBC compliance chief, Carolyn Wind, raised the issue at a board meeting she was promptly sacked. When Clark took over the role in 2010, he immediately asked for three more anti-money laundering specialists. The response from management took months. Clark rather optimistically emailed that he hoped this was not “a typical response time”. “Oh, this was express time. Trust me on that. Usually the response is “no”” came the reply.[23]

On the other hand, the staff that was employed was poorly trained and poorly led. In an exposé in Rolling Stone, one of the employees, Everett Stern, revealed the day-to-day workings of HSBC’s anti-money laundering division. Stern was hired in 2010 that is after the US regulator’s final cease and desist order against HSBC. From the beginning, he knew “there was something weird about his job”. “I had to go to the library to take out books on money-laundering… That’s how bad it was.” There were no training courses or seminars on what he was meant to be looking for. And his work principally involved “looking up the names of unsavory characters on the Internet and then running them through the bank’s internal systems to see if they popped up on any account names anywhere”. Compared to most, Stern was a dutiful employee. Most would finish all their tasks at 10.30 in the morning, “spend a few hours throwing rocks into a quarry behind the bank offices”, and then leave at around 3 in the afternoon. “If we asked for any more work… they got angry”.[24] Low staffing and poor management combined to cause enormous delays. By 2010 the department had a backlog of 17,000 alerts for suspicious behavior. In February that year, Clark wrote that the department was “in dire straights [sic] right now over backlogs, and decisions are being made by those that don’t understand the risks or consequences of their decisions”.[25]

HSBC’s money laundering was not only on a massive scale; it was systematic and well known by those higher up the bank. The serving Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, David S. Cohen stated that, “HSBC absolutely knew the risks of the business it pursued, yet it ignored specific, obvious warnings. Its failures allowed hundreds of millions of dollars in drug money to pass through its unattended gates.” And the New York District Attorney’s Office stressed that the infringements of money laundering regulations had occurred “with the knowledge, approval, and encouragement of senior corporate managers and legal and compliance departments”. Yet, when the punishment came down from the US Justice Department, it was simply a fine. Admittedly it was a large fine, but it was a fine nonetheless. First, it barely amounted to five weeks of HSBC’s profits. And second, HSBC had already put away 1.5 billion dollars in case of these so-called “emergencies”. Payment was relatively painless. Some of those named in the case had their bonuses delayed. But HSBC’s banking charter was not cancelled and no criminal charges were brought. Anti-money laundering specialists in the US were clearly surprised. “They violated every goddamn law in the book”, said Jack Blum an attorney and former Senate investigator. “They took every imaginable form of illegal and illicit business”.[26]

In fact, rather than face criminal proceedings, most of HSBC’s Mexican and US chiefs came back to the UK, where they either returned to banking and regulation or received grace and favor appointments from the UK government. Sandy Flockhart, HSBC’s man in Mexico who bought Bital with no check whatsoever, retired with a rumored £5 million in bonuses, which HSBC claimed it would try to get back but never did. He is currently chairman of the UK-based private bank Church House Trust Limited.[27] David Bagley, the head of compliance at HSBC U.S., who consistently ignored or played down US regulator’s concerns and neglected to tell HSBC US about HSBC Mexico’s problems, returned to the UK where he was rewarded with the Financial Services Authority’s top grade for money laundering detection and a job in charge of compliance at the Co-op Bank.[28] Rona Fairhead, who was in charge of the banks “risk committee”, whose job was to examine the risks to the bank’s stability, including money laundering, not only kept her job, but was also offered a £100,000 three day a week gig on the board of the BBC.[29] And the head of HSBC at the time, the Tory peer, Stephen Green, continued to operate as a UK trade minister for David Cameron’s government.[30]

“HSBC absolutely knew the risks of the business it pursued, yet it ignored specific, obvious warnings. Its failures allowed hundreds of millions of dollars in drug money to pass through its unattended gates.” Sandy Flockhart, the man who ran HSBC at the time. Now working for Oxford Capital it appears

Recently, it has become increasingly clear that UK officials were instrumental in persuading the US administration to go easy on the bank and its high-up employees. In summer 2016, the US government declassified letters between the Chancellor of the Exchequer and the US authorities. During the scandal, George Osbourne had written to Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve chairman, and Timothy Geithner, the treasury secretary to warn that prosecuting a “systemically important financial institution” like HSBC “could lead to contagion” and “very serious implications for financial and economic stability, particularly in Europe and Asia”. The UK regulator (the Financial Services Authority or FSA) proffered similar warnings. A recent US Congress report revealed that the FSA “weighed in very strongly” and “caused a firestorm” which helped persuade the attorney general to disregard the advice of his own prosecutors and not pursue criminal trials. “FSA has been on the phone for the criminal discussions,” officials wrote. “That’s what has caused the latest firestorm. The contents of that discussion are included in the Chancellor’s letter.”[31]

The story of HSBC’s money laundering reveals the ways in which international firms, including UK banks, are able to take advantage of drug prohibition to make huge profits. Over the past fifteen years, an important section of UK-Mexican relations has rested on the sustained financial exploitation of dirty cash and weak money laundering legislation. As William Black, a former regulator-turned-criminologist argues, the global financial system actually encourages such illegal and reckless behavior. Thanks to the lax regulation of the banking sector and a refusal on the part of the US and UK authorities to criminally indict bankers for fraudulent activity, banks outdo competitors by breaking the law in order to maximize profits in the shortest period. The outcome is that honest and law-abiding competitors lose their competitive advantage, while the system rewards – via bonuses and shares – dishonest acts. In short, money laundering is key to global banks gaining a competitive advantage. It is known to be illegal, but in many places it is basically allowed.[32]

The GT200 “remote substance detector”

My second story is, fortuitously, slightly simpler than the last. It concerns a UK-made “remote substance detector”, the GT200. Though it gained far less column inches than the HSBC scandal, it also demonstrates the ways in which unscrupulous UK businesses have sought to take advantage of Mexico’s war on drugs and as well as the protection offered to these companies by the UK authorities. But, the tale of the GT200, somewhat inadvertently, also reveals the flipside of the Global North’s forgiving attitude to the financial and corporate elites mixed up in the global drug war. While the bankers and businessmen, who illegally profit from the narcotics trade or its suppression, face soft or even no criminal charges, the world’s poorer inhabitants face remorseless legal systems and long prison sentences, even when - as in this case - they are completely innocent of any connection to the narcotics industry.

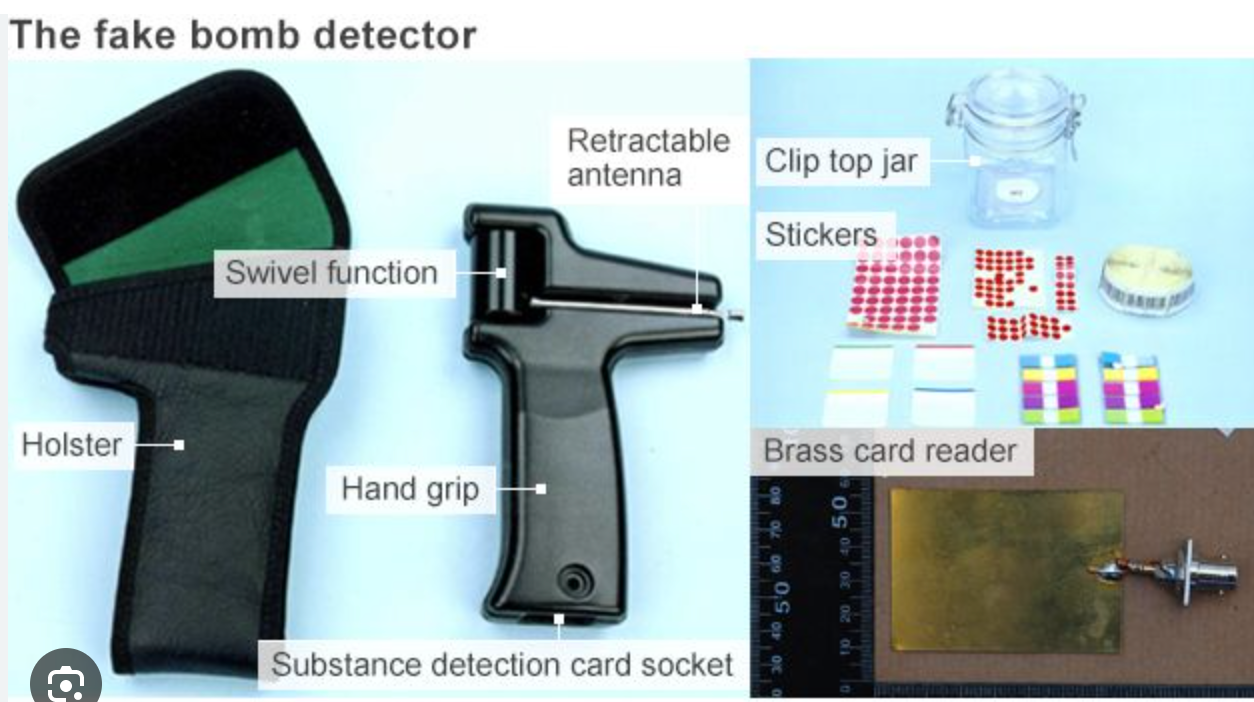

The GT200 looked simple enough. It comprised a swiveling antenna mounted via a hinge to a plastic handgrip into which different “sensor cards” could be inserted. But, the makers of the GT200, the Kent-based firm Global Technologies, claimed that the detector was the security state’s dream. According to the company head - Gary Bolton - it could detect a wide variety of items including ammunition, explosives, drugs, gold, ivory, currency, tobacco and even "human bodies" at ranges of up to 700 meters or even from aircraft at an altitude of up to 4 kilometers. The GT200’s alleged qualities attracted ample buyers. And between 2008 and 2010, Global Technologies sold well over a 1000 of these devices to Mexican federal and state administrations at a cost of $22,000 each. The Ministry of The Defense was the biggest buyer, purchasing nearly 600 machines. Federal and state authorities also used the detector in Tabasco, Sonora, Sinaloa, Durango, Michoacán and Baja California. In murder-racked Ciudad Juárez, journalists enthusiastically reported that "military squads roam the streets and go from house to house, using a molecular detector known as the GT200" to find weapons, drugs and money. In fact, the device was so regularly employed it even picked up a nickname, the Ouija del Diablo or Devil’s Ouija board. Global Technologies rewards from this selling spree were around $27 million dollars.[33]

The sales of the GT200 were directly aided by the UK ambassador in Mexico, Giles Paxman. Though memos noting that the GT200 was probably a scam had circulated throughout government departments for nearly eight years, Paxman enthusiastically endorsed the product. In a letter to the governor of Sonora, he suggested that the state government buy the product, emphasizing the “quality and excellence of the UK security industry”. The ambassador made similar introductions with the state authorities in Guadalajara, where he and his staff lined up a meeting for Bolton's company with eight officials, and also introduced him to municipal and state governments in Baja California. According to one embassy insider Bolton was even lent an office in the embassy where he could work.[34]

The problem with the GT200 miracle detector was that it was a fraud. A 2010 BBC Newsnight investigation found that the "sensor card" consisted a piece of paper sandwiched between two pieces of card cut out with a pair of scissors. The box, which was meant to contain the detection machine, contained no electronic material whatsoever. Explosives expert Sidney Alford told Newsnight: "Speaking as a professional, I would say that it is an empty plastic case." The New York Times and a handful of Mexican newspaper reports followed. Yet, despite the fact that the GT200 was shown up to be a complete fraud, an empty box with a piece of card inside, Mexican authorities continued to use the machine. The army refused scientists’ offers to test the detector and police and soldiers continued to make arrests based on the rod’s utterly fallacious findings. In fact, the machine was only stopped in December 2012, when the Attorney General concluded two years after the rest of the world that the GT200 had failed scientific tests and should not be employed by the Mexican police force.[35]

Not only did the army and the police continue to use the product, TV and newspaper media defended its use. On 17 March 2010 multiple journalists, presumably working off a government bulletin and one presumes a large cash stuffed envelope (“sin mi chayo, no me hayo”), reported that the GT200 was reasonably effective. Alberto Aguirre M. of El Economista claimed that although the machine couldn’t detect bombs, it could detect illegal substances. Doris Gomora of El Universal, repeated the same line. And Andres Becerril of Excélsior assured readers that “the secretary of defense would not have bought the detector without doing suitable tests”.[36]

Mexican authorities not only continued to use the rod but also refused to release those charged on the basis of evidence solely from the GT200. They included two brothers, from Michoacán, whose truck was pulled to the side of the road in June 2009 when the Ouija de Diablo picked up traces of narcotics amongst the cheese they were transporting for sale in the US. Without doing any further scientific checks, the two brothers were charged with being members of the Knights Templars and thrown in Puente Grande for seven years. Fortunately the two brothers had money, paid lawyers to perform tests on their cargo, and eventually got out. But many were not so lucky. In July 2015, five years after the GT200 was held up to be a fraud, Reporte Indigo used the freedom of information act to find that 1980 prisoners still languished in prison based on the machine’s accusations.[37]

In comparison, the prosecution of those that committed the fraud was relatively limited. In the UK, Bolton, the head of Global Technologies, was eventually jailed in August 2013 for seven years. And two years later, he was ordered to pay over a million pounds in compensation. In 2009, the Mexican ambassador, Giles Paxman, was swiftly removed form his post. But, he didn’t seem to suffer any professional setback. In fact, he was immediately made UK ambassador to Spain and in 2013 was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in the New Years Honors List for “services to UK interests in Spain and Mexico”.[38]

The Hay Literary Festival

My third narrative of UK-Mexican relations concerns the Hay Literary Festival and, at first, seems rather tangential to the war on drugs. Yet, like the HSBC and GT200 stories, it also highlights the ways in which the violence generated by the war has provided space for private companies in league with the UK authorities to cash in. In this case, the Foreign Office ignored concerns over human rights and freedom of expression to promote the literary festival in the Veracruz state capital of Xalapa. In doing so, the UK authorities helped prop up the regime of the now notorious governor, Javier Duarte. According to a UK embassy whistleblower, the reasons were, yet again, commercial. At the time, a UK company was attempting to gain the multimillion-pound contract for the extension of the Veracruz port. The laying on of the Hay Literary Festival was designed to secure Duarte and the federal government’s support.

In summer 2011, the organizers of the Hay Literary Festival and the UK ambassador proudly announced that the festival would be coming to Mexico. The venue they had chosen for the event was Xalapa, capital of the state Veracruz. The place seemed a fairly strange choice for the festival, because in many Mexicans’ eyes, Veracruz had become synonymous with the complete absence of freedom of expression that the Hay festival and its co-sponsor PEN International claimed to promote. Since governor Javier Duarte had come to power, in extremely dodgy elections in 2010, journalists had started to be targeted by armed groups throughout the state. First, Noel López Olguin of Horizonte and La Verdad disappeared in March 2011. His body was found beaten and tortured two months later. Then Miguel Angel López Velasco, a crime journalist for Notiver was killed together with his wife and his journalist son. Then a month later Yolanda Ordaz de la Cruz also of Notiver, was murdered and her beheaded body was found just outside Boca del Rio.[39]

Despite misgivings the festival went ahead in October that year. But over the next year, things got worse. In April 2012 Regina Martinez Perez of Proceso was murdered. And a month later, on the International Day of Liberty of the Press, the butchered bodies of two Notiver photographers, Guillermo Luna Varela and Gabriel Hugo Cordova, and the AZ reporter Esteban Rodriguez Rodriguez were found dumped in trash bags by the side of the road. According to both Governor Duarte and the local judicial authorities, the victims were all connected or mixed up in organized crime. The only murder which they didn’t try to link to organized crime - that of Regina Martinez Perez - they tried to link to a robbery or a crime of passion. But, despite these claims, journalists throughout Mexico started to link the deaths to Duarte, whom they claimed was attempting to cover up his connections to the drug cartels.[40]

Xalapa then was quite a strange choice. Facing increasing accusations of complicity in the murders, Duarte mercilessly exploited the festival for political publicity, putting some money into the celebrations, welcoming the writers to his official residence, and organizing opportune photo shoots with the English language authors. He was even photographed shaking hands with the poster boy for freedom of expression, Salman Rushdie.[41]

Furthermore, British officials were quite aware of what was going on. In March 2012 the press NGO, Article 19, called publicly for Hay to withdraw the festival. And in June 2012, just after Martínez’s murder they sent a mission to the state to investigate the situation. Yet, higher authorities within the British Embassy refused to do anything. Patrick Timmons, who worked in the embassy during the period, claims that he repeatedly brought the issue to the embassy and the British Council’s attention. The embassy staff claimed, falsely, that it had nothing to do with the festival and the head of the British Council, Lena Milosevic, explained that “journalists weren’t writers” and that the Hay was a “literary festival”.[42]

The question then is why? Why did the British government allow a murderous governor to exploit a British Council sponsored literary festival in order to whitewash his reputation for killing journalists? The answer, Timmons suggests, was money. Since 2010, Mexican officials announced that over the next 15 years, the government would invest between $1.2 and $1.8 billion in tripling the size of Veracruz port to compete with the big US Atlantic harbors. UK Trade & Investment (UKTI) was keen to gain the contracts. And In June 2014, it ran a “Ports and Trade Mission for British Companies” to Veracruz. But the efforts were to no avail. Hong Kong maritime giant Hutchison Port Holdings was awarded the contract in December 2014. It was no coincidence that at this point the Hay Festival gracefully “bowed to public pressure” and moved the festival online.[43]

Conclusions

These three stories of UK-Mexican relations offer insights into both contemporary international relations and the war on drugs. At the most prosaic level, they demonstrate, not for the first time, how international companies have managed to take advantage of heavy-handed drug prohibition policies in the Global South to make enormous profits. Most of the money from the US-backed Merida Initiative never left the US and instead has been channelled towards the purchase of US-built aircraft and surveillance software and the services of private defence contractors and NGOs. UK companies have been equally adept at exploiting the growing market. HSBC provided a means for the cartels to launder millions of dollars of money from organized crime. Global Technologies sold fraudulent detection kits to the Mexican military, landing thousands in jail. Finally, British officials used the Hay Festival in order to cosy up to a notoriously bloody local strongman and sell British industry.

But, these stories also reveal the ways in which the UK authorities – both at home and abroad – have supported such exploitation. UK foreign policy now follows a ruthlessly commercial imperative. And as the arms trade, security technology, and international finance remain key British exports, the government often defends these in the face of international pressure and human rights concerns. Finally, these cases also highlight the war on drugs’ two-tier justice system. As critics of the war have often complained, for over a century drug prohibition has principally targeted the poor, the disenfranchised, and members of certain out-of-favour racial or ethnic groups. In contrast, white, middle class or elite profiteers have suffered minimal prosecution.[44] Or in short, the rich get richer and the poor get prison.[45] As the HSBC and GT200 examples make clear, globalization means that this two-tier system now has an international aspect. HSBC bigwigs knowingly laundered millions, but were shunted sideways or upwards. In comparison, innocent Mexicans, prosecuted on the basis of evidence proffered by an empty box, have had their lives and those of their families ruined.

[1] See Enrique Peña Nieto, “The best is yet to come for Britain and Mexico”, The Daily Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/mexico/11445633/The-best-is-yet-to-come-for-Britain-and-for-Mexico.html or Diego Gómez Pickering, “Mexico: Sharing the best they have to offer”, Financial Times, http://blogs.ft.com/beyond-brics/2015/12/22/mexico-and-the-uk-sharing-the-best-they-have-to-offer/.

[2] “Peña Nieto viajó a Reino Unido con 200 personas” http://aristeguinoticias.com/1003/mexico/pena-nieto-viajo-a-reino-unido-con-200-personas-the-huffington-post-nota-y-fotos/.

[3] See the exposés at “Ayotzinapa one year on: How the UK is fuelling Mexico’s deadly war”, http://londonmexicosolidarity.org/content/ayotzinapa-one-year-how-uk-fuelling-mexico%E2%80%99s-deadly-war; “It starts here: Mexico and DSEi” https://www.caat.org.uk/issues/arms-fairs/dsei/it-starts-here/mexico; “Supplying the World’s Third Most Deadly War”, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/john-lindsaypoland/supplying-the-worlds-thir_b_8186220.html

[4] Frank Dikotter, Lars Laamann and Zhou Xun, Narcotic Culture: A History of Drugs in China (London: Hurst and Co., 2004 edn.)

[5] “London is now the global money laundering centre for the drug trade” http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/london-is-now-the-global-money-laundering-centre-for-the-drug-trade-says-crime-expert-10366262.html ; http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/uk/article4193960.ece Roberto Saviano, ZeroZeroZero (London: Penguin, 2015),.

[6] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities on Money Laundering, Drugs, and Terrorist Financing: HSBC Case History (July 12 2012), p. 237; Jill Treanor and Dominic Rishe, “HSBC pays record $1.9bn fine to settle US money-laundering accusations”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/dec/11/hsbc-bank-us-money-laundering; US Department of Justice, Statement of Facts, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/legacy/2012/12/11/dpa-attachment-a.pdf

[7] “Revela el Tesoro de EU operación de empresas del ‘Chapo’ y Cártel de Sinaloa”, http://aristeguinoticias.com/2802/mexico/revela-el-tesoro-de-eu-operacion-de-empresas-del-chapo-y-cartel-de-sinaloa/

[8] James R. Richards, Transnational Criminal Organizations, Cybercrime, and Money Laundering (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1998).

[9] Alejandro Gaviria and Daniel Mejía, Anti-Drug Policies in Colombia: Successes, Failures, and Wrong Turns (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2016).

[10] US Department of Justice, Statement of Facts, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/legacy/2012/12/11/dpa-attachment-a.pdf; Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 75, 78, 91-100.

[11] The lawyers of a handful of Texas residents murdered by the cartels recently estimated that between 2006 and 2008 the bank’s Sinaloa branches received deposits of as much as $1.1 billion of crime money.

US Department of Justice, Statement of Facts, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/legacy/2012/12/11/dpa-attachment-a.pdf and Zapata v. HSBC Holdings Plc, 16-cv-00030. U.S. District Court, Southern District of Texas (Brownsville). https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2711528/Microsoft-Word-Zapata-v-HSBC-Complaint-2016-02-09.pdf

[12] José Gregorio Pérez, Raúl Reyes: el canciller de la montaña (Bogata: Grupo Norma, 2008), pp. 125-6.

[13] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 80-5.

[14] “Mexican Fugitive and Co-Conspirator Arrested on U.S. Drug, Money Laundering Charges,” U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration press release (24/07/2007), http://www.justice.gov/dea/pubs/states/newsrel/wdo072407.html; Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 57-8; “Inside the Homes of Mexico’s Alleged Drug Lords” New York Times, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/19/garden/inside-the-homes-of-mexicos-alleged-drug-lords.html

[15] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 1-2, 100-105.

[16] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 105-111.

[17] US Department of Justice, Statement of Facts, https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/opa/legacy/2012/12/11/dpa-attachment-a.pdf

[18] David C. Jordan, Drug Politics: Dirty Money and Democracies, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press), p 103; Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 35-8; Interview with anonymous UK Civil Servant. September 2015.

[19] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, p. 59.

[20] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 53, 80-91.

[21] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 42-8, 79.

[22] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 21-4.

[23] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, pp. 27, 30.

[24] Matt Taibi, “Gangster Bankers: Too Big to Jail” Rolling Stone, http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/gangster-bankers-too-big-to-jail-20130214

[25] Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, U.S. Vulnerabilities, p. 32.

[26] US Treasury Press Release, “Treasury Department Reaches Landmark Settlement with HSBC” https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg1799.aspx ; Zapata v. HSBC Holdings Plc, 16-cv-00030. U.S. District Court, Southern District of Texas (Brownsville). https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/2711528/Microsoft-Word-Zapata-v-HSBC-Complaint-2016-02-09.pdf; Quoted in Matt Taibi, “Gangster Bankers: Too Big to Jail” Rolling Stone, http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/gangster-bankers-too-big-to-jail-20130214

[27] “Flockhart retires from HSBC but stays on board”, Evening Standard, https://www.standard.co.uk/business/business-news/flockhart-retires-from-hsbc-but-stays-on-board-7621637.html ‘Former HSBC chiefs face bonus clawbacks”, Daily Telegraph, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/9439520/Former-HSBC-chiefs-faces-bonus-clawbacks.html ; “Ex HSBC banker returns at B and C”, The Times http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/business/industries/banking/article4284191.ece

[28] James Salmon, “Co-op's judgement questioned by MPs after scandal-stricken bank hires boss who quit HSBC amid US money laundering furore”, Daily Mail, reprinted at http://www.thisismoney.co.uk/money/news/article-2846443/Co-op-hires-ex-HSBC-boss-quit-money-laundering-scandal.html#ixzz4VGeULp00

[29] Juliette Garside and Jane Martinson, “Rona Fairhead should lose BBC job over HSBC role, says influential MP”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/media/2015/mar/09/rona-fairhead-should-lose-bbc-job-over-hsbc-role-says-influential-mp

[30] Private Eye, 27 July 2012.

[31] Ruper Neate, “HSBC escaped US money-laundering charges after Osborne's intervention” The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/jul/11/hsbc-us-money-laundering-george-osborne-report

[32] Thanks to Peter Watt (University of Sheffield) for introducing me to the work of William Black. William Black, The Best Way to Rob a Bank is to Own One: How Corporate Executives and Politicians Looted the S&L Industry (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005).

[33] MVS Noticias, 20/07/2010; El Fronterizo, 21/07/2010. See the ample favourable coverage mentioned in the 2011 Senate report by W. Luis Mochán Backal, “Ciencia, Pseudociencia y Seguridad: El Detector Molecular GT200” http://em.fis.unam.mx/public/mochan/blog/20110913senado/presentacion.pdf; Luis Reyes Galindo, “Molecular Detector (Non)Technology in Mexico”, Science, Technology & Human Values, 42.1 (2017); R. Booth, “Kent Businessman Jailed for Seven Years Over Fake Bomb Detectors.” The Guardian, http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2013/aug/20/gary-bolton-jailed-seven-years-fake-bomb-detectors

[34] “UKTI Dealings with fraudster – Gary Bolton, full documents” https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/interactive/2014/jan/26/ukti-gary-bolton-documents ; Robert Booth, “UK government promoted fake bomb detectors”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/aug/20/government-fake-bomb-detectors-bolton

[35] “Export Ban for Useless “Bomb Detector”, BBC Newsnight, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/newsnight/8471187.stm; J. Jesús Lemus, La Ouija del Diablo, Reporte Indigo, http://www.reporteindigo.com/reporte/mexico/la-ouija-del-diablo

[36] Andrés Becerril, “Nueva arma de Sedena pone a temblar al narco,” Excélsior, 1 Oct. 2010, Accessed but no longer available online. Alberto Aguirre, “El Fiasco del GT200”, El Economista, http://eleconomista.com.mx/columnas/columna-especial-politica/2010/03/17/fiasco-gt200 ; Doris Gamora, “GB Alerta sobre sensor molecular” El Universal, http://archivo.eluniversal.com.mx/nacion/176349.html . See the excellent blog post on the press and the GT200 by Andrés Tonini, http://lonjho.blogspot.co.uk/2010/03/la-prensa-mexicana-defendiendo-al-gt200.html

[37] J. Jesús Lemus, “La Ouija del Diablo”, Reporte Indigo, http://www.reporteindigo.com/reporte/mexico/la-ouija-del-diablo

[38] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giles_Paxman . One wonders if this was a Foreign Office in-joke, given historian Edward Gibbon’s opinion that St George was a conman who had “accumulated wealth by the basest arts of fraud and corruption”.

[39] Dulce Ramos, “Los periodistas muertos en Veracruz”, http://www.animalpolitico.com/2012/05/siete-casos-de-periodistas-muertos-en-veracruz/

[40] Dulce Ramos, “Los periodistas muertos en Veracruz”, http://www.animalpolitico.com/2012/05/siete-casos-de-periodistas-muertos-en-veracruz/

[41] “Salman Rushdie, Xalapa y La Falsedad de Duarte” http://libertadbajopalabra.com/2015/12/01/salman-rushdie-xalapa-y-la-falsedad-de-duarte/

[42] Patrick Timmons, “British Pomp and Mexican Circumstances”, NACLA, http://nacla.org/news/2015/03/18/british-pomp-and-mexican-circumstances

[43] Patrick Timmons, “British Pomp and Mexican Circumstances”, NACLA, http://nacla.org/news/2015/03/18/british-pomp-and-mexican-circumstances

[44] For Mexico, see Isaac Campos, Homegrown: Marijuana and the Origins of Mexico’s War on Drugs (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2012); For US, the best introductions are still Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010 edn); David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (Oxford: OUP, 1999 edn.).

[45] Taken from Jeffrey Reitman and Paul Leighton, The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison: Ideology, Class, and Criminal Justice (London: Routledge, 2012 edn).